Current affairs 20th and 21st April 2019

Current Affairs and Editorial discussion from various national daily newspapers

Current affairs 20th and 21st April 2019

Prelims

Phishing

Why in news?

Wipro, India’s fourth largest IT services exporter, faced an advanced phishing attack on its IT systems.

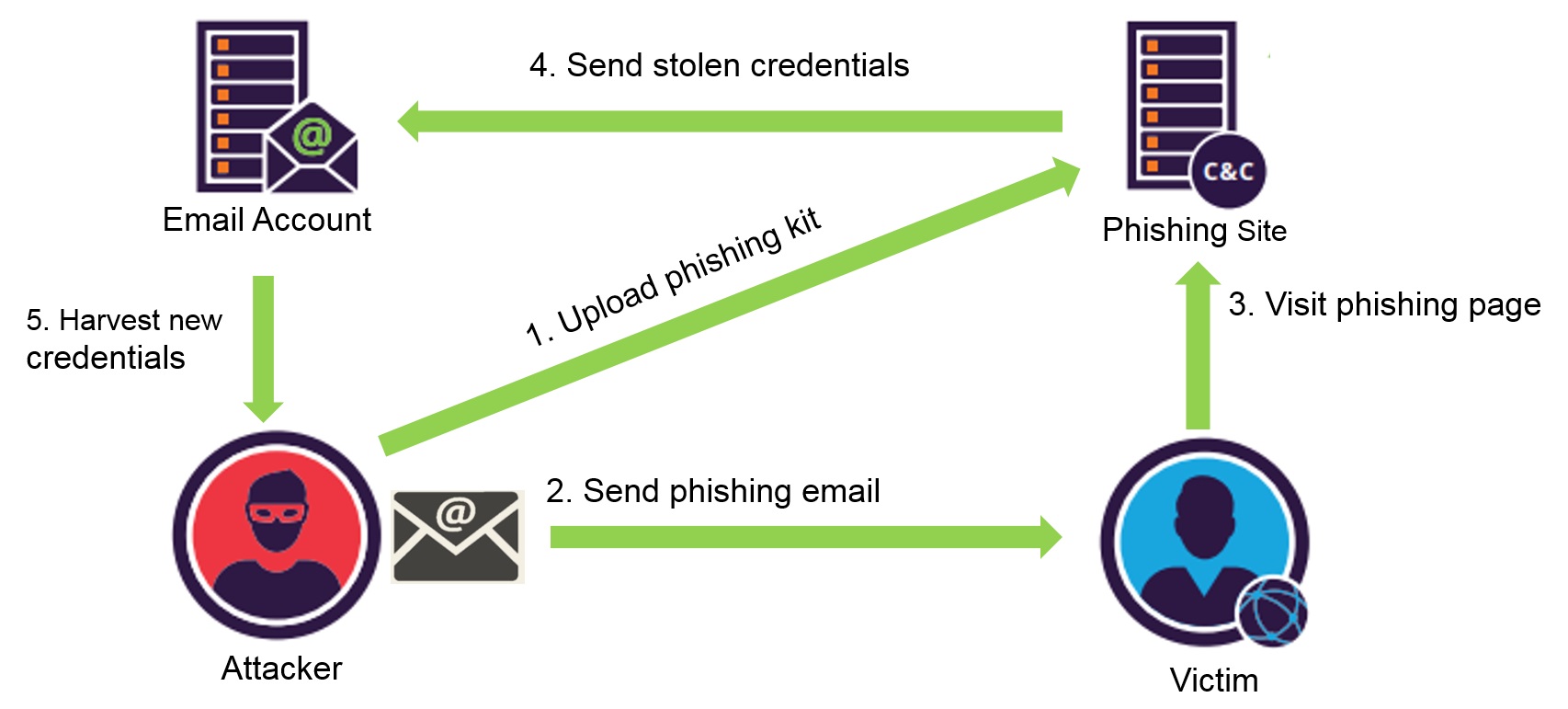

What is phishing?

Phishing is the fraudulent attempt to obtain sensitive information such as usernames, passwords and credit card details by disguising as a trustworthy entity in an electronic communication.

Mains

Models for rating agencies

Why in news?

With credit rating agencies coming under watch for delayed action in recent debt defaults by various companies, the government is examining whether the ‘issuer pays model’ can be streamlined and investor or regulator pays model be put in place.

What is investor pays model?

The issuer pays model – wherein the company whose securities are being rated pays the rating agency – has time and again come under criticism for apparent conflict of interest.

What’s going on?

The Reserve Bank of India and the government in 2017 planned to set up a pooled fund for paying rating agencies, but it was put on the back burner.

In light of the perceived laxity of rating agencies during recent defaults by IL&FS group, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance in its February report recommended the government to look at putting in place an investor or regulator pays model in case of rating agencies. Even as industry players argued in their discussions with the finance ministry that issuer pays model is time tested and used by most countries, the government and the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) are reviewing the regulations to incorporate the Committee’s suggestions and to further strengthen the regulatory framework, government sources said.

How many rating agencies are there in India and what has SEBI done to strengthen them?

Currently, there are seven rating agencies registered with SEBI, out of which three are listed on stock exchanges. These include CRISIL, CARE Ratings, ICRA, India Ratings and Research, Brickwork Ratings India, Acuite Ratings & Research, and Infomerics Valuation and Rating.

To strengthen the rating agencies framework, SEBI last year revised its Credit Rating Agencies Regulations, 1999, when it raised minimum net worth criteria for rating agencies to Rs 25 crore from Rs 5 crore and asked agency promoters to have minimum shareholding of 26 per cent. The markets regulator also mandated agencies to separate ratings and non-ratings business. Sources said further changes are being planned by the finance, SEBI and Reserve Bank of India to the regulations.

These agencies provide ratings for securities being offered in initial public offers, rights issues, bank loans, commercial papers, non-convertible debentures and fixed deposits among others.

Principles of natural justice

Why in news?

Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi on the Supreme Court Bench, which heard the “extraordinary” session on Saturday into the online publication of sexual harassment allegations levelled against him by a former apex court employee, raises two pertinent questions.

What are the questions raised?

One, did the Chief Justice of India (CJI) become a judge in his own cause by being part of the Bench? After all, the allegations directly pertain to him. Two, is there a formal procedure to deal with allegations of sexual harassment against the CJI?

Over the years, two basic principles have been recognised as fundamental in the doctrine of natural justice. The first is ‘nemo judex in causa sua’, that is, ‘no man shall be a judge in his own case’; the second is ‘audi altarem partem’, that is, ‘hear the other side’.”

In 2018, speaking for the Supreme Court of India in Lok Prahari v. State of U.P. & Ors., Justice Gogoi recognised the seven principles of public life in the report by Lord Nolan and recapitulated them as “Selflessness, Integrity, Objectivity, Accountability, Openness, Honesty, and Leadership.”

In the circumstances of this case, where the charge of sexual harassment, victimisation and intimidation has been made against a person holding the highest judicial office of the country, it is imperative that for the credibility of the institution, and confidence of the people in the judiciary as well as for the right to justice of the woman complainant, no hearing presided by the CJI ought to have been held.

In the inhouse procedure for dealing with complaints against Supreme Court and High Court judges, it is the CJI who “examines” whether a particular complaint is frivolous. There is no word in it on how to deal with a complaint against the CJI. Under the Gender Sensitisation and Sexual Harassment of Women at the Supreme Court of India (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal), Regulations of 2013, it is again the CJI who sets up the Gender Sensitisation and Internal Complaints Committee.

Fixed maturity Plans

Why in news?

Earlier this month, Kotak Mutual Fund informed investors in its Fixed Maturity Plans (FMPs) that it would not be able to fully redeem investments made in two series of the FMPs. Separately, HDFC Mutual Fund also announced the extension of one of its FMP schemes, which was due for maturity on April 15, by 380 days.

What are FMPs?

Debt mutual funds, unlike equity MFs, invest in debt securities issued by companies (both publicly listed and privately held) and governments. FMPs, in turn, are a class of debt funds that are closeended: one can only invest in them at the time of a new fund offer and they come with a specified maturity date, much like a fixed deposit (FD). However, in contrast to deposits, FMPs don’t offer a guaranteed return but only pitch an indicative yield that the investor then takes a bet on. What the investor forgoes in terms of liquidity compared with an FD, she hopes to make good via the marginally higher returns that the fund’s investments in higher yield debt instruments such as commercial paper, corporate bonds and nonconvertible debentures (NCDs) could potentially earn it. Additionally, investments in FMPs are more tax efficient, since there are indexation benefits linked to capital gains, as opposed to tax on interest income in the case of an FD. FMPs, however, like other debt funds come with their own set of risks: the most significant ones are interest rate risk and credit risk.

Indoor pollution

India can achieve its air quality goals if it completely eliminates emissions from household sources. A recent study has pointed out that the use of firewood, kerosene and coal in the households contributed to about 40% of the PM 2.5 pollution in the Gangetic basin districts. This number varied across the country but household emissions remained one of the major culprits behind air pollution. The analysis was carried out by researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Delhi in collaboration with University of California in Berkeley. According to the study, if all households transitioned to clean fuels, about 13% of premature mortality in India could be averted.

In many villages, they still use firewood for room heating and water heating. People prefer cheap wood fuel despite LPG being provided to many households,”